The Emmott Lab uses proteomics to study viruses and how they replicate. In particular RNA viruses important for human and animal health such as Norovirus and SARS-CoV-2. Research in the lab is what is known as ‘basic science’: early-stage investigations which lay the groundwork for more applied or clinical studies. By learning the fundamentals of how these viruses replicate and interact with the cells they infect, we can learn how to treat infections, design better vaccines or antiviral drugs, or even convert viruses from pathogens into useful gene therapy or anticancer tools. We also regularly collaborate to help other researchers apply the mass spectrometry methods we use to their own study systems.

The research the lab does falls into three main themes:

RNA virus replication

Within an infected cell, most of what the virus needs to replicate and produce more virus it takes from the host cell. These can be resources such as tRNA, nucleotides, or large protein complexes such as the ribosome that the virus can use or modify for its own purposes. However, the machinery necessary to replicate the virus genome has to be provided by the virus as this is not a process that occurs within a normal uninfected cell. In the case of positive-sense RNA viruses, initial translation of the viral genome by the ribosome produces the proteins needed for viral replication. This is most commonly in the form of a viral polyprotein.

RNA virus replication is very error-prone compared to DNA replication, so RNA viruses have developed a number of means to compress the maximum amount of protein-coding information into a very small genome. A very common method is for a positive-sense virus to produce a polyprotein. This is a long protein containing a number of different functional domains, separated by protease cleavage sites. The protease is typically contained as part of this polyprotein. Over the course of infection, the polyprotein is cleaved by the protease, with different sites cleaved at different rates. The different cleavage products produced by this process (called precursors) can have different functions depending on their current cleavage state. For example, different precursor forms of the protease can localize to different parts of the cell, controlling when cleavage takes place. As a result, the composition of the viral replication complex, comprising both the viral and cellular proteins needed to replicate the viral genome changes over time, and these changes can be linked to changes in replication complex function.

In the Emmott lab, we are interested in these dynamic changes in replication complex composition throughout infection, and how these can be linked to altered replication complex function. We are also interested in how heterogenous this process is on a single-cell level. Whilst single-cell RNAseq has begun to be applied to studies of virus replication, it cannot give insight into post-translational events such as the protein cleavage that is critical in these polyprotein-based systems. We instead apply single-cell proteomics, using the SCoPE2 method Ed helped develop in his time in the Slavov Lab, alongside more traditional mass spectrometry, virology, mol. bio. and imaging approaches to investigate this phenomena.

Protein cleavage

As described in the section above on RNA virus replication, many positive-sense RNA viruses replicate through the use of polyprotein, which is cleaved by a viral protease. However, it is common for viral proteases to also target cellular proteins for cleavage, and this can play an important role in the viruses ability to take over cellular functions, and hinder an infected cells attempts to resist infection or signal neighboring cells.

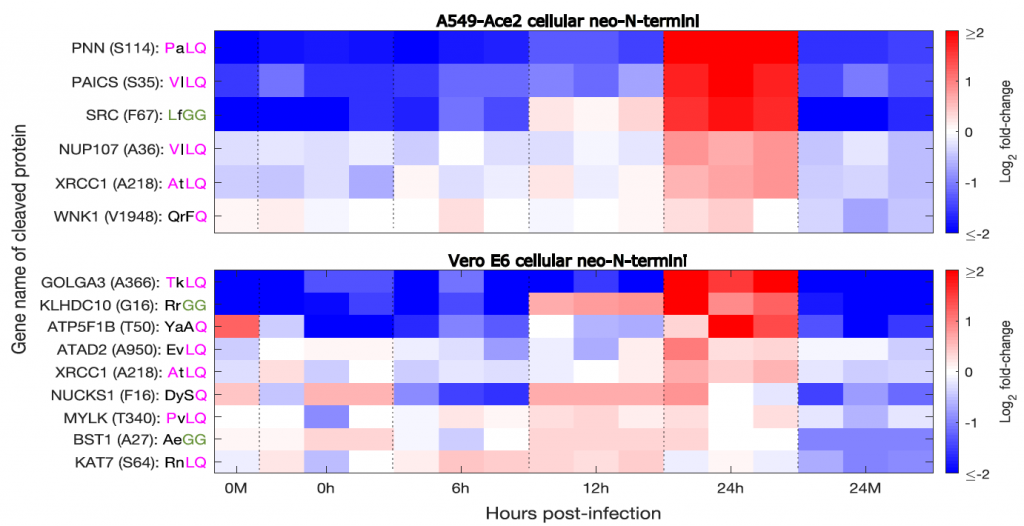

Cellular proteins cleaved during SARS-CoV-2 infection (Meyer et al. 2020, bioRxiv) |

Viral proteases can cleave cellular proteins to subvert cellular processes such as protein synthesis, cutting off the host cells ability to make its own protein while leaving all the necessary machinery present to make viral proteins. Similarly, cellular proteins important for immune signaling can be cleaved as a mechanism to inhibit the immune response. We recently used mass-spectrometry-based methods to study protease activity in SARS-CoV-2 infection, identifying 14 potential substrates of the SARS-CoV-2 proteases as well as numerous novel cleavage sites within viral proteins. We found that these cellular substrates were essential for efficient SARS-CoV-2 replication, and could be inhibited by drugs in current use to treat other conditions, suggesting that targeting cellular protease substrates may represent a therapeutic strategy to treat viral disease. These same methods can also inform us as other proteolytic cleavage/processing and degradation events occurring within infected cells.

In the lab, we are interested in identifying and characterising cellular targets of viral proteases. We are also interested in their cleavage dynamics throughout infection, and how this is regulated by different forms of the viral protease(s).

Developing proteomic methods

We apply and develop new LC/MS-based proteomic methods in support of the labs work on virus replication and virus-host interactions. This includes single-cell proteomics, including prioritized single-cell proteomics to try and study virus replication (and its associated post-translational modifications) at single-cell level. We are especially interested in studying proteolytic cleavage and degradation of large viral polyproteins and their cleavage intermediates (precursors).

More broadly, we collaborate with other groups to apply proteomics to their own research questions, and collaborate with clinicians and industry to help take our basic science findings and translate these into assays that can be applied in the clinic.